On 18 April 1978, I received a phone call from Dad. Uncle Max had killed himself. Earlier that morning, Max was to meet with attorney George Knell at the office of Knell & Freehafer before they would walk the short distance to the Richland County Courthouse. Some weeks before, Max's wife Mary had filed for divorce after enduring a thirty-year marriage that had produced no children and countless arguments. That morning the court would render the final verdict in the matter. When Max did not show up and did not answer repeated attempts to contact him by phone, the firm sent a young law clerk over to my Grandmother's house to find him.

|

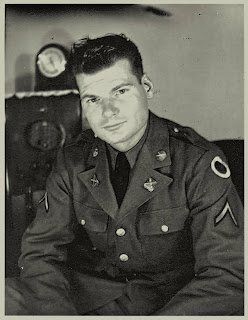

| Russell Maxton Case |

Max lived with Grandmother during the pendency of the divorce proceedings while Mary continued living in their marital home. Three days before that morning, Grandmother, and presumably Max, marked her 85th birthday. At her age, walking up and down the stairs had become difficult. So now she slept downstairs. Max slept alone on the second floor in a room Grandmother called "the boys' room." The reference was to Grandmother's brothers who had slept there as children. Her boys, save for Wendell, had never lived in that house. Nonetheless, the room's closets contained items that had belonged to them, brought there by Grandmother when she moved there after the war. Max's army uniform with his 37th "Buckeye" Infantry Division patch was among them.

The "boys' room" was my room during my summer stay there in 1956. As an eight-year-old, I regarded the uniform in the closet with reverence and awe. It was heavy and smelled of wool, and I viewed it as something of importance, something to be treasured. The shoes on the floor were still spit-shined. It was the uniform Max had on when he came home from the war. He wanted to look outstanding for his folks and Mary. In his letters home, he never described the war in the Pacific. During periods of combat operations when there was no time to write home, he would apologize for not having written sooner, adding, "we've all been pretty busy here lately." For his homecoming, he wanted to look his best, happy and in good health. Like a lot of GIs, he avoided talking about the war except in general terms. The details he kept locked up somewhere deep inside. Twenty-eight-year-old Russell Maxton Case, who walked off the ramp of the USS General William Mitchell onto the streets of San Fransisco on Thursday, 6 December 1945, was not the same lad drafted into the Ohio National Guard in 1941.

When the law clerk arrived, he stood at the bottom of the stairs and called out to Max several times. When he got no reply, he climbed the stairs and entered the "boys' room." Scattered on Max's bed and the surrounding floor were tens of thousands of dollars. The money was Max's life savings, which he had withdrawn from his savings account the day before. Max lay face-up on the bed, amid the cash, in a pool of blood. He had been a parole officer and owned a snub-nosed revolver. Earlier that morning, Max had pressed its muzzle beneath his lower jaw, pointing upward through his head, and pulled the trigger.When the law clerk discovered the scene, he ran downstairs and called for an ambulance. Soon after, the ambulance arrived, as did the police. The ambulance attendants removed Max's body, the police took possession of the pistol, spent bullet casing, and cash, and everybody left the blood-soaked bedding for Grandmother.

Back at the courthouse, everything had changed. Mary was no longer Max's wife; she was his widow. The court dismissed the divorce case. I suppose that the cash removed by the police was eventually turned over to Mary, or paid into his estate, pending administration. The same for the pistol.

Dad and I arrived at Grandmother's house the following day. We found her alone, seated in a chair at the kitchen table, weeping. Too weak to climb the stairs, she never saw the scene that greeted the law clerk. She just waited for us to come up from Tennessee. We tried to comfort her and listened to her account of what happened. She thought she heard a noise upstairs but was unsure since she was so hard of hearing. She did not realize it was a pistol shot. When the law clerk arrived, she told him to go upstairs for Max since they needed to hurry. She had no clue that anything was wrong until the law clerk came running down the stairs.

After talking with Grandmother, Dad and I climbed the narrow staircase to the second floor. Neither of us said anything on the way up. Filled with dread at what we would see, we nevertheless walked straight into the "boy's room" as soon as we reached the top of the stairs. It was worse than I expected. The blood where Max's head lay as he fell back on the bed was not merely a stain. Instead, it was a thick coagulated puddle that soaked through the sheet to the mattress below, a sight that I will never forget. It was not entirely smooth. It contained some small lumps here and there. Perhaps bits of skull and brain. I did not look closely to find out because I didn't want to know. I felt like I was looking at something too personal. Too private. Something that belonged to Max and was not for me to see. It is difficult to explain my feelings at the moment.

My father and I stripped the sheets and pillowcases off the bed and lay them bundled up on the floor, with the bloodiest areas in the middle of the bundle. We did this so Grandmother would not see the blood when we took the sheets downstairs. Beneath the sheets, the mattress had a large stain where blood had soaked through the sheet. We called out to Grandmother to please leave the kitchen and sit in the dining room for a few minutes. We wrestled the cumbersome mattress down the narrow stairs and through the kitchen to the back porch when she did so. We hesitated there a moment to catch our breath and readjust our grip. Then we carried it across the driveway out to the garden. We went back upstairs and brought down the lower mattress, then the pillows and bundled sheets. We placed everything in a pile on the first mattress. In the garage, we found rakes and a can of gasoline. We soaked the bedding with the gas and set it alight.

It took a while to burn and needed constant raking to keep the fire from dying out. In about a half-hour, it was all just a smoldering pile of ashes. We worked in outward silence. We didn't discuss Max or Grandmother. We just went about our task solemnly, reverentially. The only sounds were the crackle of the flames and the scraping of the rakes. Yet, our minds were not silent. At least, not mine. I thought of Max, Grandmother, Dad, and Mary. I struggled to understand how things got to this point. It was all an immense gray sadness. I knew that trips to Ohio would never be the same again. The happiness died with Max.